Criminal Justice Month is well underway, and we believe this is a time to amplify our voice around the issues and strategic ways to partner in justice transformation. Our GOSO team is particularly excited to see that Meisha Porter — a native New Yorker and long-time educator — will become the first Black woman to take the helm of New York City’s public schools on March 15th. We look forward to her leadership as many Black and brown children are slipping through the cracks of the educational system.

- The New York City public school system is the largest in the United States, serving more than 1.1 million students across 1,700+ public schools.

- 85% of all juveniles who are justice-involved are functionally illiterate; and 70% of the people in the U.S. prison system can’t read beyond a fourth grade level.

- Our schools are struggling to meet the needs of underserved communities. And rather than being a safe haven for learning – especially for children with academic and emotional needs – many schools have become a pipeline for prisons.

How did we get here?

New York City teachers and school administrators deal with a host of issues and challenges — there’s no denying that fact. Compounding an already difficult job, educators don’t have the necessary tools and resources to address some of the problems they’re seeing. The pressure that teachers face to keep pace with the school’s curriculum can also put struggling students at a disadvantage. As a result, far too many children with learning and emotional needs have needless encounters with the criminal justice system because schools turn to the police rather than trained specialists.

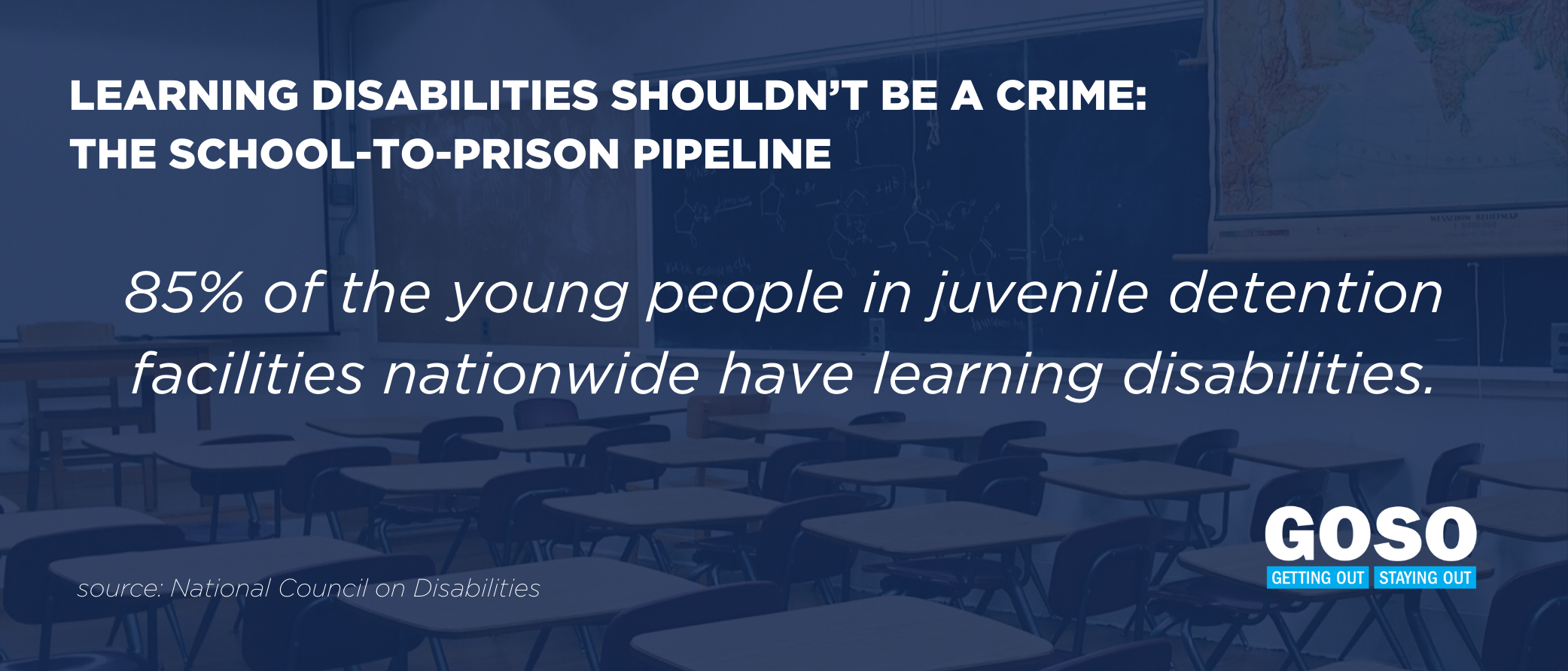

By some estimates, 85% of the young people in juvenile detention facilities nationwide have learning disabilities, which makes them eligible for special education services. Tragically, only 37% of these young people received specialized services while in school. Likewise, more than 50% of GOSO’s participants are struggling to overcome a mental health issue, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, or a substance abuse disorder.

Education versus incarceration

Over the years we have been encouraged to see that crime rates among juveniles are on the decline. But there’s a worrisome counterpoint that can’t be ignored: School disciplinary policies are moving in the opposite direction, with out-of-school suspensions more than doubling since the 1970s. And according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, Black students are 3x more likely to be suspended or expelled than white students.

Further, zero-tolerance school policies have required schools to adhere to stringent, pre-defined punishments that fail to account for individual circumstances. The irony is that these “get tough” policies have been doing more harm than good.

“Students regularly report that their past schools did not take into account the circumstances that contributed to their academic struggles,” remarked Lauren Bricker, LCSW, GOSO’s Director of Educational and Vocational Programs. “Instead of providing students with the resources that would help mitigate their problems, they were met with punishment for ‘acting out’ or feeling disengaged from school.”

Ending the pipeline to prison

GOSO’s work with justice-involved young men has shown us that all is not lost. Many of the students that come to our school program have had significant interruptions in their education due to being part of the criminal justice system. When people are released, they are often behind when it comes to schooling; and they return to a school system where they are older than their peers but behind academically.

As a result, GOSO has collaborated with the NYC Department of Education to create Pathways-to-Graduation (P2G), which is a high-school equivalency program at our on-site educational center. In a recent study of alumni GOSO participants who have been out of our program for 2+ years, those involved in our P2G education program, regardless of whether they completed the program or attained a high school equivalency diploma, have an average recidivism rate of 8%. The impact of quality education for the age and population we serve cannot be overstated. But work like this requires a village. In addition to our P2G staff, we have a team of exceedingly dedicated professionals who provide services to assist with mental health, court advocacy, job placement, housing, and more. Our aim here is to support the whole person.

With a changing of the guard at NYC public schools, we hope that Ms. Porter finds the necessary resources to better support our city’s children, particularly those struggling with very real educational and emotional needs.

Schools with zero tolerance policies that focus on punishment need to change course by giving more consideration to the root of the problem at hand. When disciplinary matters surface, restorative justice approaches should be used to hold people accountable while looking at the full circumstances of a situation. As Ms. Bricker observed, ‘Simply focusing on punishment leaves the student feeling there is a lack of justice. Restorative justice approaches give the student a chance to tell their side of the story and give suggestions as to what they believe is a fair and just resolution.”

Having a learning disability or living with childhood trauma should not be criminalized; and children deserve a better future than the one prison affords.

GET INVOLVED: Help GOSO recognize National Criminal Justice Month. SHARE this important op-ed and JOIN us for our upcoming events.