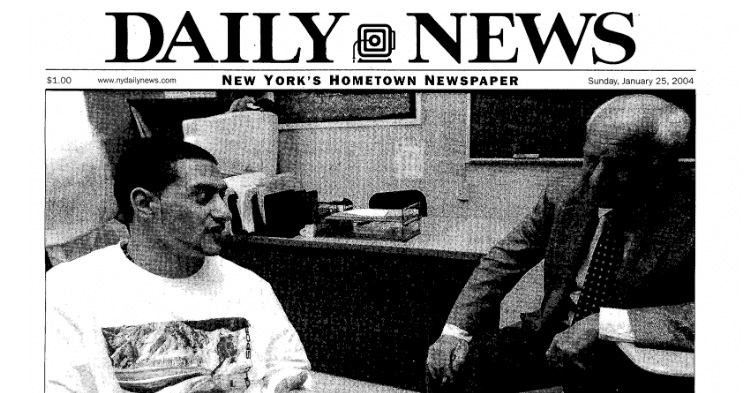

DOING BUSINESS AT RIKERS ISLAND. Entrepreneur succeeds in keeping ex-convicts free of trouble after they leave prison

By Nicole Bode / originally published November 15, 2006

In the three years since he started working with Rikers Island inmates, Mark Goldsmith has drastically increased the odds of success for hundreds of newly released young men in danger of slipping right back into jail.

Of the more than 400 former inmates who have passed through Getting Out and Staying Out, his prison-transition program, 250 have been released so far. Only 10 have returned to prison, a fraction of the 66% of inmates who typically end up back behind bars. “To me, it’s society’s last chance. Either grab them here, or you lose them,” said Goldsmith, 70, a Manhattan businessman who launched the nonprofit program after acting as co-principal for a day inside Horizon Academy, Rikers’ high school for 18- to 21-year-olds, alongside lawyer Marvin Schecter.

Troubled by the rising number of inmates and the shrinking resources to serve them, Goldsmith turned his entrepreneurial skills toward the public sector: He set out to teach inmates responsible business and life skills to keep them from ending up back in jail. After gaining permission from both the Correction and Education departments, Goldsmith began traveling to Rikers several times a week to talk with interested inmates. He challenged them to immediately start thinking about what they would do upon their release from prison – even if that was still years away. He set up a three-part program designed to take them from incarceration to in transition to in the community.

The program exploded. Dozens, then hundreds of inmates ages 18 to 24 were lining up to talk about their dreams and goals with the friendly, straight-shooting ex-cosmetics mogul. “These young men begin to see someone cares about them,” Goldsmith said. Goldsmith’s first goal is to have students get serious about their education – pushing them to get their general equivalency diplomas and coaching them when necessary. Once they have that, he works with them to pursue additional education, whether it’s a trade school when they’re released or a correspondence degree from Ohio University’s College Program for the Incarcerated.

He also brings in other coaches – professionals like himself – to speak candidly with the inmates and expose them to additional points of view. The program fills a void in the prison-release system, because most programs target inmates upon their release, rather than in jail, he said. “A lot of programs wait till the day they’re ready to leave, and that’s a huge mistake,” Goldsmith said. When appropriate, he and his colleagues appear in court on behalf of some of their clients, urging more lenient sentences in recognition of the inmates’ achievements.

When sentenced inmates cycle out of Rikers and into upstate prisons, Goldsmith and the others who work with him write them regularly, checking up on their progress and sending them books to fuel their development. By the time they’re ready to be released, Goldsmith amps up the correspondence. If need be, he tracks down their lawyers and asks for their release dates. Other times he calls their homes. “I couldn’t believe he called me,” said Charles Smith, 22, who was shocked to find a message from Goldsmith when he returned home to Washington Heights from prison in May. “He’s a man of his word. Two years later, he still remembers me. It’s not just business.”

Goldsmith urges his clients to make his East Harlem office their first stop upon release. They deal with emergency needs first: housing, mental health or drug treatment referrals or anger management. They are also given an “essential tools” bag, including an alarm clock, MetroCard, notepad, pens, a professional résumé and condoms – “so they’ll be safe.”

The discreet storefront office, which opened in 2005, has tinted windows for added privacy and a number of Internet-ready computers so clients can hunt down jobs, write résumés and research their field of interest. Goldsmith, who served several years in the Navy and spent 35 years in the cosmetics industry, might seem like an unlikely champion for inner-city youth. But he sees it differently. “I worked during the day and went to school at night,” he said. “And that’s what I advocate to them because it makes them feel better.”

But Goldsmith is modest about his role in his clients’ success. He credits the work of countless contributors, including Gloria Ortiz, the principal of Horizon Academy, for welcoming him into her school; staffers from the Correction Department for making room for the program, and his funders for making the enterprise possible. As to how a white-haired, suit-wearing man earns the trust of inmates, Goldsmith’s clients don’t think twice. “He steps to you right,” said Armel Johnson, 21, of lower Manhattan. “He was down-to-earth. He related to our problems. After a month being with him, he showed me I was worth more than I thought myself.”

Clients can’t say enough about Goldsmith, praising his positive attitude, nonjudgmental style and consistent follow-through. “He’s like a role model for us people who didn’t have a father,” said Joel Leon, 20, of the Bronx. “He showed you there was another way of life.”

Goldsmith is hoping the program will grow even larger – possibly becoming a template for other jails and prisons across the city – now that Mayor Bloomberg’s anti-poverty program reps have shown a distinct interest in its success. “You need an entrepreneur; there’s no question about it,” Goldsmith said. “You need somebody with a good business sense, a good heart and soul and someone who believes in second chances. That’s what it takes to do a job like this.”

For more information on GOSO contact Info@gosonyc.org